THE BAGGAGE OF AN AFGHAN PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATE

THE BAGGAGE OF AN AFGHAN PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATE

By Ronald Sandee

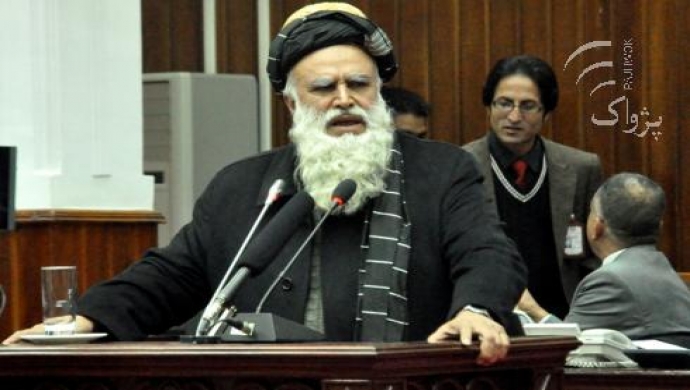

Last month, Abd al-Rasul Sayyaf, an influential member of the Afghan parliament who changed his name to Abd al-Rab Rasul Sayyaf, announced his bid to become the next president of Afghanistan. Although Sayyaf is an important powerbroker and a key ally of current Afghan President Hamid Karzai, he is looked upon by the Afghan people with suspicion, and not without good reason. For some, his influence is seen as a counterweight to the Afghan Taliban’s seemingly indefatigable aspirations to reclaim control of Afghanistan. For others, his Islamist views aren’t radically different than the views of the many Salafist-Jihadi terrorists to whom Sayyaf has lent his support.

Although Sayyaf is an ethnic Pashtun, he cannot rely on the Pashtun tribal clan structure to rally massive support for his candidacy. Hailing from the Paghman area on the outskirts of Kabul, Sayyaf never had a real powerbase. While this didn’t prevent him from becoming a highly-influential figure during the Afghan Jihad of the 1980s, polling data recently referenced by the Economist suggests he may be better positioned to assist a runoff candidate in upcoming elections than to run as a viable candidate himself.

Not unlike a number of Afghan presidential candidates, Sayyaf is running with a great deal of baggage in tow. So much that Western diplomats active in the region should be looking with cautious optimism at polling data that indicates the presidency is not in the cards for him.

Born in 1946, Sayyaf earned his Bachelor’s in Religious Studies from Kabul University and his Master’s from al-Azhar University in Cairo. While in Egypt he learned to speak Arabic fluently and fell under the influence of the Muslim Brotherhood, eventually joining the Afghan variant of the Muslim Brotherhood founded by Burhannuddin Rabbani.

During the Afghan Jihad, Sayyaf founded the Ittehad-i-Islami Baraye Azadi Afghanistan resistance organization, or Islamic Union for the Liberation of Afghanistan. He became the point man for the Saudis when it came to the matter of distributing their aid for the Afghan Jihad, and Sayyaf was very active in the recruitment of foreign fighters. The Saudis awarded Sayyaf the prestigious King Faisal Intellectual Prize in 1985.

Al-Sada was one of Sayyaf’s important jihadi training camps at this time. Run by Afghan Jihad leader Abdallah Azzam, it was in al-Sada that 9/11 mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohamed (said to have served as Sayyaf’s secretary for some time), Riduan Isomuddin (aka Hambali) and Abdurajak Abubakar Janjalani (founder of the Philippines-based Abu Sayyaf terrorist organization) met and became friends. Sayyaf was also instrumental in helping Usama bin Laden establish one of his first camp inside Afghanistan, Maasadat al-Ansar (aka the Lion’s Den). The enterprise we now call al-Qa’ida was created there on September 10, 1988.

According to a leaked JTF-GTMO Detainee Assessment of Khalid Sheikh Mohamed, KSM heard a speech by Sayyaf in 1982. Sayyaf was preaching on jihad, and KSM subsequently decided he wanted to join the jihad in Afghanistan. Shortly after hearing Sayyaf, KSM joined the Muslim Brotherhood and became even more determined to join the jihad. KSM went to Afghanistan and attended the Sada training camp managed by Azzam on behalf of Sayyaf. “At the conclusion of his training in 1987, KSM worked for the magazine al-Bunyan al-Marsous, produced by Sayyaf’s group.” Around the same time KSM arrived in Afghanistan, Hambali traveled from Malaysia to the Sada camp for training.

After the Russians left Afghanistan, Sayyaf was poised to become Afghanistan’s prime minister, but ended up serving as interior minister for a short time.

Since the fall of the Taliban regime in late 2001, Sayyaf has been a crucial powerbroker in Afghanistan. As a member of parliament and the chairman of the International Relations Committee of the Lower House, Sayyaf — once staunchly anti-American — has become perhaps one of the more rational voices in parliament and an almost moderate force in the often emotional inner workings of Afghan politics. “Now at the twilight of his career, Sayyaf may be realizing he needs to expand his contacts in order to stay relevant,” stated a 2009 diplomatic cable from the U.S. Embassy in Kabul.

Sayyaf is certainly a master of public relations. Formerly known as an enemy of Afghanistan’s Shiite Hazaras, in 2005 Sayyaf managed to garner their support for his bid to become speaker of the Lower House of the Afghan parliament. However, his involvement in a dispute over property rights in his native Paghman area outside Kabul made headlines around the same time, and tarnished his carefully managed political brand.

It remains to be seen whether Sayyaf will have in the next president the same sort of resource for asserting his influence that Sayyaf has had in Hamid Karzai. Still, it’s a safe bet that, for the foreseeable future, Sayyaf will continue to be a stalwart mouthpiece of views that would be labeled radical if voiced here in the West. Indeed, although a number of Afghan Taliban leaders refer to him as “the manifestation of Satan,” their worldviews aren’t exactly what anyone can reasonably call disparate.