ON A NATO-MEMBER STATE’S SPONSORSHIP OF TERRORISM

ON A NATO-MEMBER STATE’S SPONSORSHIP OF TERRORISM

By Michael S. Smith II

Among the forms of state sponsorship of terrorism discernible in the 21st Century, passive sponsorship is an issue that requires more attention from counterterrorism officials. This form of state sponsorship of terrorism has been a crucial source of fuel for the world’s newest jihad theater, “al-Sham,” which is a vital incubator for jihadis’ aspirations to attack NATO-member states on both sides of the Atlantic. Thus it is seemingly paradoxical to find a NATO-member state has been a key purveyor of this increasingly important form of support to al-Qa’ida-affiliated elements — current and former — which are among the most effective fighting forces active in Syria. Even though many NATO members may share that country’s desire to see Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad relieved of power.

As is reflected in recent events and intelligence, two prominent terrorist organizations active in Syria, ISIS and Jabhat al-Nusrah, seek to widen the areas of their operations in Syria’s neighborhood. Further, according to America’s top intelligence officials, Jabhat al-Nusrah, the official manager of al-Qa’ida’s Syria portfolio, is preparing jihadis to conduct attacks in the West. As Director of National Intelligence James Clapper put it, “this is a huge concern.”

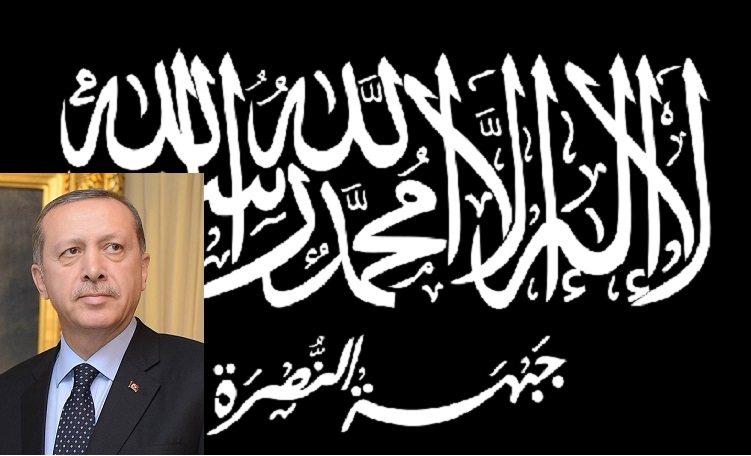

Meanwhile, it is the NATO-member state of Turkey — whose policies adopted to enhance the capabilities of the anti-Assad opposition in Syria have bolstered these terrorist organizations — that serves as more than a rear operating base for campaigns waged by ISIS and al-Nusrah inside Syria, and an important hub for these groups’ recruitment activities. Equally important to the larger security picture at hand, Turkey is a key ingress and egress point for both terrorists and many prospective terrorist recruits in their travels between the world’s newest jihad theater and the West.

This situation is not the stuff of coincidences manifest by Turkey’s proximity to the conflict(s) underway in Syria. Nor does this situation stem from incapacity on the part of Ankara to deter or disrupt such activities. Nor has this situation resulted from ignorance on the part of Ankara — the Erdogan administration is very much aware of how Turkish territory is being utilized.

Ultimately, this situation is a direct result of the Erdogan government’s passive sponsorship of terrorism. More specifically, this situation is a result of Mr. Erdogan’s accommodation of jihadist elements that pose the most severe threats to the safety and security of Turkey’s “allies” in NATO. Namely the Global Jihad movement’s torchbearer: al-Qa’ida.

Indeed, despite a long history of incidents involving al-Qa’ida in Turkey, the root issue is knowing toleration.

In a discussion of passive forms of state sponsorship like “knowing toleration” contained in a 2008 analysis paper published by the Brookings Institution, former CIA Middle East political analyst Dan Byman offered the following insights (emphasis added):

Some governments may make a policy decision not to interfere with a terrorist group that is raising money, recruiting, or otherwise exploiting its territory. In essence, the regime wants the group to flourish and believes that by not acting it can help it do so. Syria did this shortly after the US invasion of Iraq, allowing jihadists, ex-Ba‘thists, and others to organize from Syrian soil.

A clear picture of the Erdogan government’s sponsorship of al-Qa’ida-affiliated elements active in Syria may be had by replacing a few words in this description:

Some governments may make a policy decision not to interfere with a terrorist group that is raising money, recruiting, or otherwise exploiting its territory. In essence, the regime wants the group to flourish and believes that by not acting it can help it do so. [Turkey] did this shortly after the [civil war broke out in Syria], allowing jihadists … and others to organize from [Turkish] soil.

The Obama administration is not blind to this situation. During a May 2013 meeting with Mr. Erdogan held in the Oval Office, President Obama bluntly voiced concerns about the Erdogan government’s indiscriminate support for the Syrian opposition.

Months earlier, the US government reportedly designated Jabhat al-Nusrah a terrorist group in December 2012 to send Ankara a message about its support for such groups. The decision to designate al-Nusrah was met with criticism from Turkish officials.

It is not yet clear whether increased raids on al-Qa’ida safe houses and operations focused on disrupting ISIS’s activities in Turkey ahead of the 2014 elections have been conducted to furnish a good cop façade for the Erdogan government. Or has there been a sincere pivot toward meaningful enforcement of Turkey’s official counterterrorism policies in response to further criticism the Erdogan government encountered last fall?

Regardless of whether Mr. Erdogan has finally arrived at a sober realization of the enormous problems which may arise from his Syria policies, the effects of his government’s on-again-off-again policy of inaction — in the very least — in response to al-Qa’ida-affiliated jihadis’ uses of Turkish territory are clear: Terrorists have benefitted immensely. As one such jihadi told the press with a wink during an interview at a hotel in the Turkish border town Kilis last fall, whether Turkey has intended to be or not, “she has been very good to us.”

Certainly, the situation in Turkey — one which intelligence indicates has substantial implications for the security of a number of NATO-member states — is quite alarming on several levels. Still, it is important to note the apparent irony of a NATO-member state serving as a sponsor of violent Islamist extremists designated terrorists by other NATO members is not new. Mr. Erdogan’s active support of Hamas has been known to Western leaders for some time.

As this situation reveals, insomuch as a new approach to analyzing the complex issue of state sponsorship of terrorism is still needed, so too are more persuasive tools that will help responsible world leaders deter and disrupt it. Indeed, in the case of the “moderate” Erdogan government, past and present behaviors alike suggest talk alone is unlikely to resolve the problem at hand.