HOW TRUMP ADMIN POLICIES ARE REALLY USED AS RECRUITMENT TOOLS BY ISLAMIC STATE

HOW TRUMP ADMIN POLICIES ARE REALLY USED AS RECRUITMENT TOOLS BY ISLAMIC STATE

Michael S. Smith II

Days after he was sworn in to serve as America’s 45th commander-in-chief, President Trump inked an executive order resulting in a temporary “ban” on travel to the United States for residents of war-torn, majority-Muslim countries in which the Islamic State and other terrorist groups are particularly active. Many — if not most — journalists employed by major news organizations have amplified analysis which holds that the Islamic State will convert this into a recruitment tool. As an analyst focused on the group’s influence operations, I believe it is reasonable to anticipate the Islamic State will seek to use this policy to bolster its appeal among prospective recruits. But in a manner which is more useful to the group than many journalists, prominent members of Congress and cable news pundits seem to grasp. Meanwhile, rather than hyping more flimsy analysis focused on how the Islamic State will use the “travel ban” to build support, journalists and news producers working to help the public understand the implications of US policies would be wise to consider the “travel ban” is not the only policy concept introduced by the Trump administration that the Islamic State can use to convince prospective recruits the group is worthy of their support. Indeed, it is likely far bigger problems will be generated by another policy prescription which is receiving much less coverage than the “travel ban.”

The prevailing analysis of implications of the “travel ban” holds that the Islamic State will use this policy to convince residents of various countries that (a) US policies which create hardships for Muslims reflect Americans’ “hatred” of Islam — a common assertion found in most Salafi-Jihadist groups’ propaganda for decades — and (b) the Islamic State is thus worthy of their support, because the group is waging a jihad against the United States and its allies. While the Islamic State, like al-Qa’ida and most other Salafi-Jihadist groups, does indeed seek to harness an array of grievances concerning US policies to build support in the Muslim world, this analysis falls short of accounting for the chief set of perceptions which the group seeks to engineer in order to enhance its capabilities to outbid al-Qa’ida and other competing groups for support: Strength and durability in the face of better-equipped, technologically-superior enemies, especially the US.

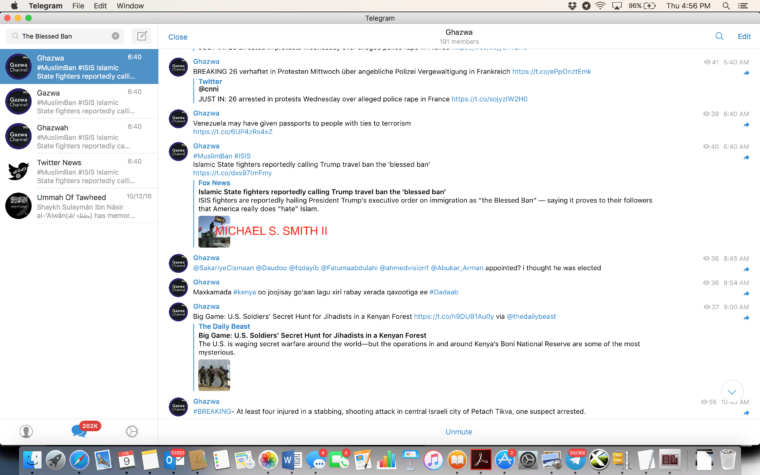

Since the “travel ban” was implemented, the Islamic State has published issues of two of its most well-known publications, al-Naba, a weekly Arabic-language newspaper, and Rumiyah, which has replaced the group’s best-known publication, Dabiq. Therein, mentions of the executive order were notable by their absence. Meanwhile, while covering developments in Mosul, New York Times reporter Rukmini Callimachi has determined the narratives Islamic State members and supporters are developing to try to convert the “ban,” which they’re reportedly referring to as “The Blessed Ban,” into a recruitment tool revolve around the group’s insistence on claiming it is a more competent and dedicated enemy of the US than competing Salafi-Jihadist groups. (Note: As the screenshot used as the lead image for this piece reflects, a search for “The Blessed Ban” and hashtag variants thereof on 100, plus pro-IS Telegram channels, a number of which are popular English-language channels, yielded only posts noting Rukmini’s tweets about the topic.)

As noted on Rukmini’s Twitter feed, the “travel ban” narrative employed by Islamic State supporters in Iraq emphasizes the group’s capabilities to threaten Americans. Contrary to conventional wisdom, it would appear the group is not focused on highlighting hardships caused by the “ban.” Arguably, that would create a mixed signal, as, in the eleventh issue of Dabiq, the Islamic State decried fleeing to the West from conflict zones where it claims to be establishing a “caliphate” is a “dangerous major sin.” This, while using an image of a child who drowned as their family fled Syria to seek refuge in Europe to highlight what the group described as wrath meted out for what they note may be considered “apostasy.”

As many terrorism analysts are aware, references to “The Blessed Ban” described by Rukmini reflect a familiar form of framing that emphasizes the Islamic State’s strength. This sort of framing emerged in early pieces of Islamic State propaganda. For example, in the fourth issue of the group’s flagship publication, Dabiq, while channeling guidance proffered by deceased American-born al-Qa’ida cleric Anwar al-Awlaki, the Islamic State asserted one may identify which group is most practicing of the “faith” — thus worthy of support from the “faithful” — by examining which group the enemies of the “faithful” have oriented most of their counterterrorism resources against, due to threats posed by it: “To paraphrase Shaykh Anwar al-Awlaki, if one wants to know the people of truth, then let him observe where the enemies’ arrows are aimed. Most of them — if not all — are now pointed at the Islamic State, its leaders, soldiers, and subjects.”

Here, it is important to note that, with respect to the question of how the Islamic State continues to build and reinforce support, a maxim of the nonprofit sector applies: People give to winners. A similar maxim is found in the compilation of reports produced in 2014 by a working group of terrorism studies scholars and analysts who sought to help MajGen Michael K. Nagata understand what he called Islamic State’s “intangible power”: Success breeds success.

Ultimately, the implementations of extraordinary policies like this “travel ban” constitute a form of success for the Islamic State in that these policies demonstrate the group is successfully generating fear manifesting in drastic measures taken to (try to) limit the group’s capabilities to threaten Americans. In other words, the group derives enhanced perceptions of legitimacy in the eyes of would-be supporters vis-à-vis unprecedented policies that highlight the group’s success terrorizing its enemies. Indeed, unlike many terrorist groups, the Islamic State has defined its members as “terrorists” in official propaganda. For example, in the video titled “Kill Them Wherever You Find Them,” which featured missives from participants in the November 2015 attacks in Paris, Abdelhamid Abaaoud, a coordinator of the attacks whose work coordinating other attack plots in Europe was covered in an issue of Dabiq published online in February 2015, asserted: “we are terrorists. We are the ones who terrorize the disbelievers.” (For analysts, Abaaoud’s message was clear: As has been the case in other official propaganda materials produced by the Islamic State, the group is drawing contrasts with al-Qa’ida and aligned groups which refuse to join the Islamic State by suggesting it is a more dedicated, competent threat to the West.)

Meanwhile, an even greater form of success the Islamic State can use to enhance its abilities to recruit is seen in the Trump administration’s proposed US-Russia counter-Islamic State partnership. The spirit of relations between our countries have for decades been characterized as competitive. Therefore, Islamic State propagandists will almost certainly seize the opportunity to highlight the group poses so much more of a threat to the international system than al-Qa’ida and other not-yet-aligned groups that relations between competing major world powers are changing in order to (try to) generate a more effective military campaign against the group. For many of the battle-hardened jihadis that have not yet joined the Islamic State — and whose support will be essential if the group hopes to defend and expand control of major population centers in various countries where it is active beyond Iraq and Syria — this turn of events will further make the Islamic State look like the true “vanguard” of the Global Jihad movement. In other words, the group which is most deserving of their support.

Certainly, there is an abundance of ignorance and myopia evident in various policies aiming to reduce threats posed by the Islamic State which have been implemented and proposed by the Trump administration. As I noted in a report recently published by Time, movement of tons of cocaine into the US each year highlights the ease with which a determined terrorist group could smuggle 100 terrorists into the country across our northern and southern borders, or through waterways on board leisure watercraft. Meanwhile, as I noted while participating as a panelist during a recent event focused on the Trump administration’s foreign policy agenda that was hosted by Foreign Policy’s analytics division, the US will gain very little from a counterterrorism partnership with Russia. Further, such a policy will be converted into a far more powerful recruitment tool for the Islamic State than the “travel ban,” which is unlikely to prevent the group from deploying terrorists into the US.