CVE?

CVE?

By Michael S. Smith II

Since 2014, the US-designated foreign terrorist organization commonly referred to as ISIS, or ISIL has used American companies’ social media platforms and file-sharing sites to wage the most aggressive and effective worldwide recruitment and incitement campaign of any terrorist group in history. During the past year, several of these companies have touted their efforts aimed at “Combatting Violent Extremism,” as the title of a February 2016 Twitter blog post concerning the suspensions of 125,000 Twitter accounts reads. However, as was highlighted in a report published by The Wall Street Journal in April 2016 that covered some of my work tracking Islamic State propagandists’ activities on Twitter, this suspension campaign is not a sufficient deterrent. Indeed, efforts to disrupt the Islamic State’s use of popular social media and file-sharing sites to build and reinforce support have yet to deter the terrorist group from harnessing American companies’ technologies to — among other purposes — identify and cultivate what officials at the National Counterterrorism Center refer to as “fence sitters.” In other words, people who have yet to do one of two things to affirm their allegiance to the Islamic State’s leader, as directed by him: Make hijrah (emigrate to the so-called “caliphate” to help the Islamic State defend and expand territorial holdings), or kill as many Westerners as possible at home. Meanwhile, remarkably little attention has been paid to the ongoing exploitations of these technologies by other Salafi-Jihadist groups, along with influential clerics who proffer narratives engineered to build support for them. This narrow focus on the Islamic State could ultimately serve to bolster the group’s recruitment and incitement capabilities.

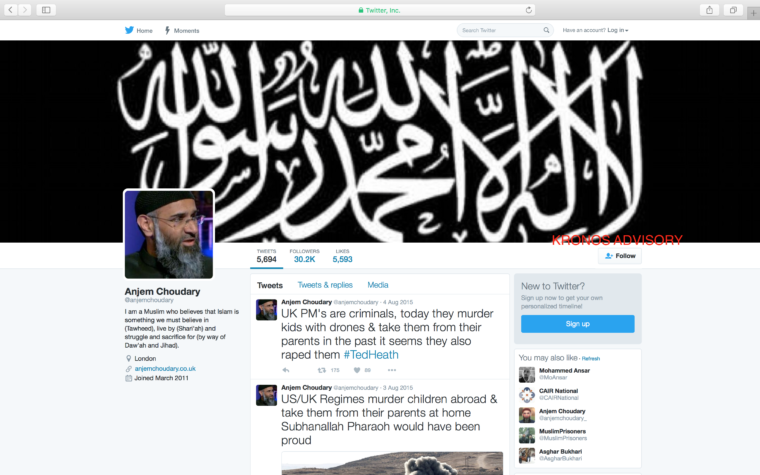

That much is left to be desired by Twitter’s so-called “Combatting Violent Extremism” program is perhaps best highlighted by the fact that Twitter did not suspend an account used by the Salafi-Jihadist cleric Anjem Choudary to engage with a global audience of prospective Islamic State supporters until today. Choudary was convicted in the UK of building support for the Islamic State. Like thousands of other Islamic State supporters, Choudary used Twitter to enhance the Islamic State’s abilities to incite violence far from its ever-expanding primary areas of operation. Analysts familiar with narrative sets engineered by the Islamic State to accelerate the radicalization process culminating in a resort to violence could see that many tweets viewable on the cleric’s account were intended to augment the Islamic State’s calls for its supporters to execute terrorist attacks in the West.

Although the last tweet viewable on Choudary’s account was posted in August 2015, until today, Islamic State recruiters could continue using his account to identify prospective recruits by monitoring the activities of the account’s followers, especially those who retweeted, liked, or replied favorably to Choudary’s tweets. Those who doubt Islamic State members are ever vigilant on social media might wish to consider that Briton hactivist turned terrorist Sally Jones, an Islamic State member whom Secretary of State John Kerry designated a specially-designated global terrorist, tweeted a screenshot of one of my tweets concerning her return to Twitter earlier this year.

Choudary is but one of many high-profile clerics who have used Twitter to build support for a terrorist group. Other notable examples of such activities may be seen in the uses of Twitter to reach a global audience by two Jordan-based al-Qa’ida-affiliated clerics, Mohamed al-Maqdisi and Abu Qatadah. With followings of more than 49,700 and 58,200 accounts, respectively, each Twitter account managed by these al-Qa’ida enablers has attracted more followers than the official Twitter account managed by Special Presidential Envoy to the Coalition to Counter ISIL Brett McGurk.

As noted by Islamic State members running Telegram Messenger channels that are being used to bolster the group’s influence operations in the cyber domain: While Twitter is more aggressively suspending Islamic State-linked accounts than ever before, suspension of accounts used to augment al-Qa’ida’s online influence operations is evidently not an objective that has been assigned equal priority.

In recent days, a large group of Twitter accounts managed by members of al-Qa’ida’s global support base have been used to broadcast links to the latest video message from al-Qa’ida emir Ayman al-Zawahiri, who, in a September 2013 memo titled “General Guidelines for Jihad,” reaffirmed for al-Qa’ida’s operational planners, along with al-Qa’ida supporters the world over that killing Americans remains a top priority for the group. Despite having largely failed to meet expectations generated by such statements, continuity of the group’s aspirations to achieve this objective may be seen in the ongoing production — and promotion via Twitter — of such propaganda materials as Inspire. Equally notable is the recent message from Usama bin Ladin’s son, Hamza, which was used to reassure al-Qa’ida’s global audience the terrorist group intends to seek revenge for the killing of its founding leader.

One link to the latest video message from al-Zawahiri distributed by accounts comprising al-Qa’ida’s network on Twitter directs interested parties to a copy of the video published via YouTube. A subsidiary of Google, YouTube was used by the American-born al-Qa’ida cleric Anwar al-Awlaki to call for attacks in the United States, such as the one executed at Fort Hood by an Army officer who contacted al-Awlaki via e-mail beforehand. Although YouTube has diligently worked to rapidly delete Islamic State propaganda videos, much like Twitter, YouTube has apparently not assigned equal priority to efforts to deny al-Qa’ida the ability to use its popular video file-sharing site. Indeed, at this writing, the aforementioned copy of al-Zawahiri’s latest message that was uploaded to YouTube five days ago has been viewed more than 16,000 times.

In February 2016, a senior official involved with NCTC’s online countering violent extremism programs asked if I would be willing to map networks of Islamic State “fence sitters” on Twitter. Were it not for the fact this official was a Twitter investor I would have been surprised that more was not being done by NCTC to identify prospective Islamic State recruits within such an easy-to-monitor space of the Internet. Yet what is surprising is that, after having brought the Twitter account managed by Mohamed al-Maqdisi to the attention of Twitter, as well as senior counterterrorism officials — not just special agents at FBI — al-Maqdisi’s account remains active weeks later. In addition, although it was brought to the attention of these same officials nearly eight hours ago, the aforementioned copy of al-Zawahiri’s latest message remains viewable on YouTube.

Ultimately, it would seem officials tasked with engaging with popular social media and file-sharing companies about terrorists’ uses of their technologies may have failed to consider that, as the Islamic State is demonstrating it is more capable of stewarding the Global Jihad movement’s agenda than al-Qa’ida, those technologies may be increasingly important tools used by Islamic State recruiters to identify al-Qa’ida members and sympathizers who can be convinced to either defect, or, in the cases of al-Qa’ida sympathizers in the West, execute attacks used to further help the Islamic State outbid al-Qa’ida for support. Indeed, al-Maqdisi, who was for a time the spiritual guide for the founding leader of the group now known as the Islamic State, may be an unwitting source of leads for Islamic State recruiters who can use his account to identify either disillusioned al-Qa’ida members, or aspirant jihadis deemed unfit for membership in al-Qa’ida.